Who owns the world’s wealth?

A new report by Oxfam shows that one percenters will soon own more than half the world's wealth and recommends solutions to close the gap between the world's ultra rich and desperately poor.

By 2016, more than 50 percent of the world’s wealth will be owned by the richest one percent of people in the world.

In a report released today, entitled “Wealth: Having it all and wanting more,” anti-poverty group Oxfam says the percent of global wealth held by the world’s most affluent people reached 48 percent last year, up from 44 percent in 2009. If current trends persist, the richest 1 percent will own more than 50 percent of the world’s wealth by 2016, suggesting that the rate at which the ultra rich are gaining control of the world’s wealth is increasing as well.

“The scale of global inequality is quite simply staggering,” Winnie Byanyima, Oxfam’s executive director, says in a letter addressed to world leaders attending the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, this week. “The gap between the richest and the rest is widening fast.”

The world’s richest added $92 billion to their collective fortune in 2014, according to the Bloomberg Billionaires Index. Meanwhile, more than a billion people live on less than $1.25 per day, according to Oxfam.

Income inequality is likely to be a topic of focus at the forum. President Barack Obama is expected to make it a central point of his State of the Union speech on Tuesday. But, as Oxfam illustrates in its report, the lobbying power of the world’s top corporations could present a “major barrier” to any kind of global tax reform.

The report also recommends stricter enforcement of laws preventing corporate and individual tax dodging, closing tax loopholes, more investment in free public services, and a shift in taxes toward capital and wealth to help fix the problem.

President Obama wants to increase the top tax rate on capital gains and dividends to 28 percent from 23.8 percent. The rate was 15 percent when he took office in 2009. He also wants to impose capital-gains taxes on asset transfers at death, ending what the White House calls “the largest capital gains loophole.”

Getting richer faster

The report found that global wealth is becoming increasingly concentrated among a small wealthy elite. The wealth of the richest 80 individuals in the world is now the same as that owned by the bottom 50 percent of the global population, meaning that 3.5 billion people share, between them, the same amount of wealth as that of these extremely wealthy 80 people.

“In 2010, it took 388 billionaires to equal the wealth of the bottom half of the world’s population; by 2014, the figure had fallen to just 80 billionaires,” according to the report.

Who are these top one percent of the world’s rich? In 2014 there were 1,645 people listed by Forbes as being billionaires. This group of people is far from being globally representative. Almost 30 percent of them (492 people) are citizens of the United States. Over one-third of billionaires started from a position of wealth, with 34 percent of them having inherited some or all of their riches. This group is predominately male and graying, with 85 percent of these people aged over 50 years and 90 percent of them male

The report found that most of these wealthy individuals have generated and sustained their wealth through interests and activities in just a few important economic sectors.

In March 2014, 20 percent (321) of them were listed as having interests or activities in, or relating to, the financial and insurance sectors, the most commonly cited source of wealth for billionaires on the Forbes list. Since March 2013, there have been 37 new billionaires from these sectors, and six have dropped off the list. The accumulated wealth of billionaires from these sectors has increased from $1.01 trillion to $1.16 trillion in a single year; a nominal increase of $150 billion, or 15 percent.

The richest billionaires in this category include names like Warren Buffett, Michael Bloomberg, Carl Icahn, Prince Alwaleed Bin Talal of Saudi Arabia, George Soros, Joseph Safra, Luis Carlos Sarmiento, Mikhail Prokhorov, Alexey Mordashov and Abigail Johnson (one of the few women on the Forbes list).

Between 2013 and 2014 billionaires listed as having interests and activities in the pharmaceutical and healthcare sectors saw the biggest increase in their collective wealth. Twenty-nine individuals joined the ranks of the billionaires between March 2013 and March 2014 (five dropped off the list), increasing the total number from 66 billionaires to 90 in 2014, making up 5 percent of the total billionaires on the Forbes list. The collective wealth of billionaires with interests in this sector increased from $170 billion to $250 billion, a 47 percent increase and the largest percentage increase in wealth of the different sectors on the Forbes list.

Men like Dilip Shanghvi of India, Patrick Soon Shiong of the U.S., and Ludwig Merckle and Curt Engelhorn of Germany make their billions in pharmaceuticals, while Hansjoerg Wyss of Switzerland and Gayle Cook, a woman from the U.S., are in business creating medical devices. Stefano Pessina of Italy meanwhile, who saw the largest gain in wealth between 2013–14 in this sector ($6.4–10.4 billion, or a 63 percent increase in wealth), is the largest single shareholder of Chicago-based Walgreen Co. and a drug-store mogul.

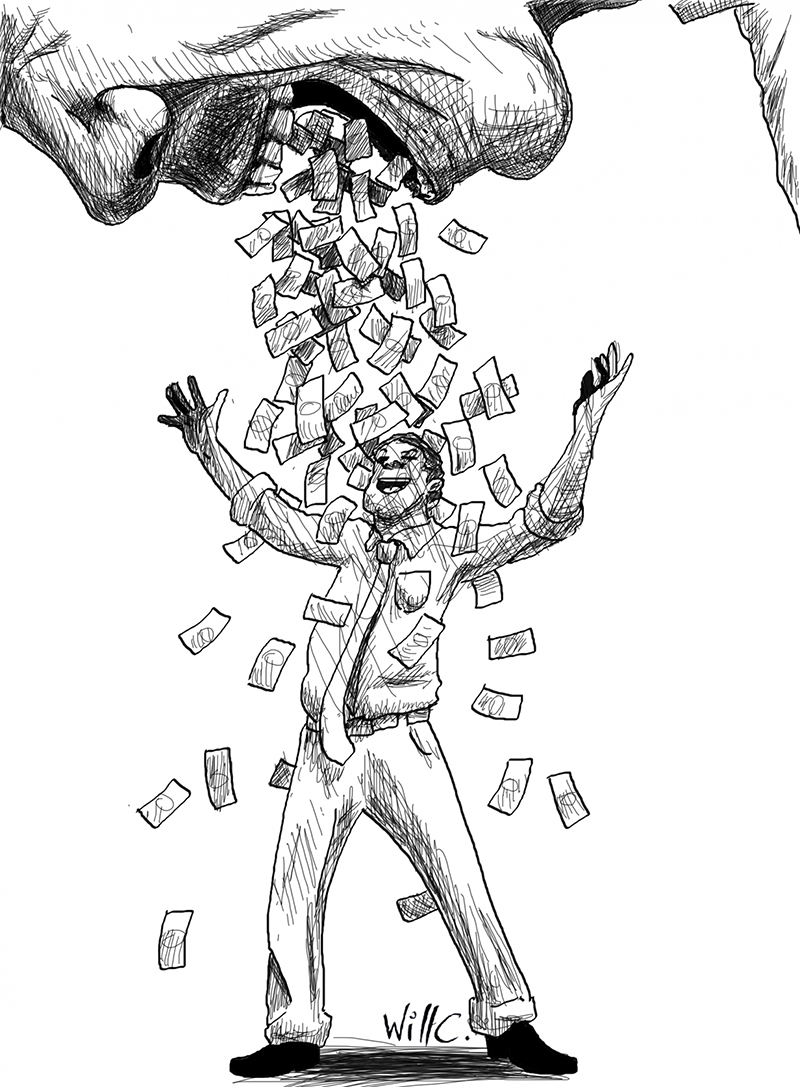

Cartoon by Will Caron

Lobbying for wealth

Companies from both the finance and pharmaceutical sectors spend millions of dollars annually on lobbying. “During 2013, the finance sector spent more than $400 million on lobbying in the U.S. alone, 12 percent of the total amount spent by all sectors on lobbying in the U.S. in 2013,” according to the report. “In addition, during the election cycle of 2012, $571 million was spent by companies from this sector on campaign contributions.”

According to the Centre for Responsive Politics, the financial sector is the largest source of campaign contributions to federal candidates and parties. Billionaires from the U.S. make up approximately half of the total billionaires on the Forbes list with interests in the financial sector. Their lobbying pays off. In 2013, the number of U.S. finance billionaires increased from 141 to 150, and their collective wealth from $535 billion to $629 billion; an increase of $94 billion (17 percent) in a single year.

“While corporations from the finance and insurance sectors spend their resources on lobbying to pursue their own interests and, as a result, go on to increase their profits and the associated wealth of those individuals involved in the sector, ordinary people continue to pay the price of the global financial crisis,” according to the report. “While the financial sector has recovered well as a result of this bailout, median income levels in the U.S. are yet to return to their pre-crisis levels.”

The cost of the bailout of the financial sector to U.S. taxpayers was calculated to be $21 billion. The ongoing cost to the tax payer for “systematically important financial institutions”—in other words those that are too big to fail—has been estimated by the International Monetary Fund to be $83 billion every year.

During 2013, the pharmaceutical and healthcare sectors spent more than $487 million on lobbying in the U.S. alone. This was more than was spent by any other sector in the U.S., representing 15 percent of the $3.2 billion total lobbying expenditures in 2013. In addition, during the election cycle of 2012, $260 million was spent by this sector on campaign contributions.

“While millions are being spent on lobbying by pharmaceutical and healthcare companies and billions being made by individuals associated with these companies, a health crisis has erupted in West Africa,” reads the report. “The Ebola virus has … threaten[ed] the lives and livelihoods of millions of people in Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia in 2014.

According to the report, companies in this sector have responded positively to the Ebola crisis: some pharmaceutical companies are investing in research to find a vaccine, the full costs of which are not yet known. The three pharmaceutical companies that are members of the International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers & Associations (IFPMA) and that have made the largest contribution to the Ebola relief effort, have collectively donated more than $3 million in cash and medical products.

But the amount of money that has been spent on Ebola and other activities that have a broader benefit to society needs to be looked at in the context of these companies’ expenditures on corporate lobbying to earn influence for their own interests. These three companies together spent more than $18 million on lobbying activities in the U.S. during 2013.

“To put the funding for the Ebola crisis in perspective, the World Bank estimates that the economic costs to Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone was $356 million in output forgone in 2014, and a further $815 million in 2015 if the epidemic is slow to be contained,” according to the report. “The largest increase in wealth between 2013 and 2014 by a single pharma-related billionaire could pay the entire $1.17 billion cost for 2014–15 three times over.”

The billions that are spent by companies on lobbying, giving them direct access to policy and law makers in Washington and Brussels, where the European Union is headquartered, is a calculated investment. “The expectation is that these billions will deliver policies that create a more favorable and profitable business environment, which will more than compensate for the lobbying costs,” reads the report.

“In the U.S., the two issues which most lobbying is reported against are the federal budget and appropriations and taxes,” the report continues. “These are the public’s resources, which companies are aiming to directly influence for their own benefit, using their substantial cash resources. Lobbying on tax issues in particular can directly undermine public interests, where a reduction in the tax burden to companies results in less money for delivering essential public services.”

Wealth gap myth

Today’s report insists that rising inequality is not, in fact, inevitable, as many media outlets claim (media outlets which are all owned by five powerful companies owned by one percenters). In October 2014, Oxfam launched its Even It Up campaign, which calls on governments, institutions and corporations to tackle extreme inequality. This briefing provides further evidence that we must build a fairer economic and political system that values every citizen. Oxfam is calling on world leaders, including those gathered at the 2015 World Economic Forum Annual Meeting in Davos, to address the factors that have led to today’s inequality explosion and to implement policies that redistribute money and power from the few to the many.

Some of Oxfam’s suggestions include making governments agree on a post-2015 goal to eradicate extreme inequality by 2030; public disclosure of lobbying activities; ending the gender pay gap; increasing minimum wages towards living wages; shifting the tax burden away from labor and consumption towards wealth, capital and income from these assets; national wealth taxes; a tax reform process where developing countries participate on an equal footing; stopping the use of tax havens, including through a blacklist and sanctions; making companies pay based on their real economic activity; stopping new and reviewing existing public subsidies for health and education provision by private for-profit companies; excluding public services and medicines from trade and investment agreements; increased investment in medicines, including in affordable generics; and excluding intellectual property rules from trade agreements.

A full list of Oxfam’s recommendations to governments, institutions and corporations can be found in the report Even It Up: Time to end extreme inequality published in October 2014.